How tech giants track you across the web, even if you don't use their apps

Excellent reporting by BBC's Thomas Germain in his latest Keeping Tabs column:

"TikTok collects sensitive and potentially embarrassing information about you even if you've never used the app. [...] The issue centres around major changes to TikTok's "pixel", a tracking tool that companies use to monitor your online behaviour.

When it's shoe store data, the information might be innocuous. But I've reported on TikTok's data collection for years and pixels can collect extremely personal information."

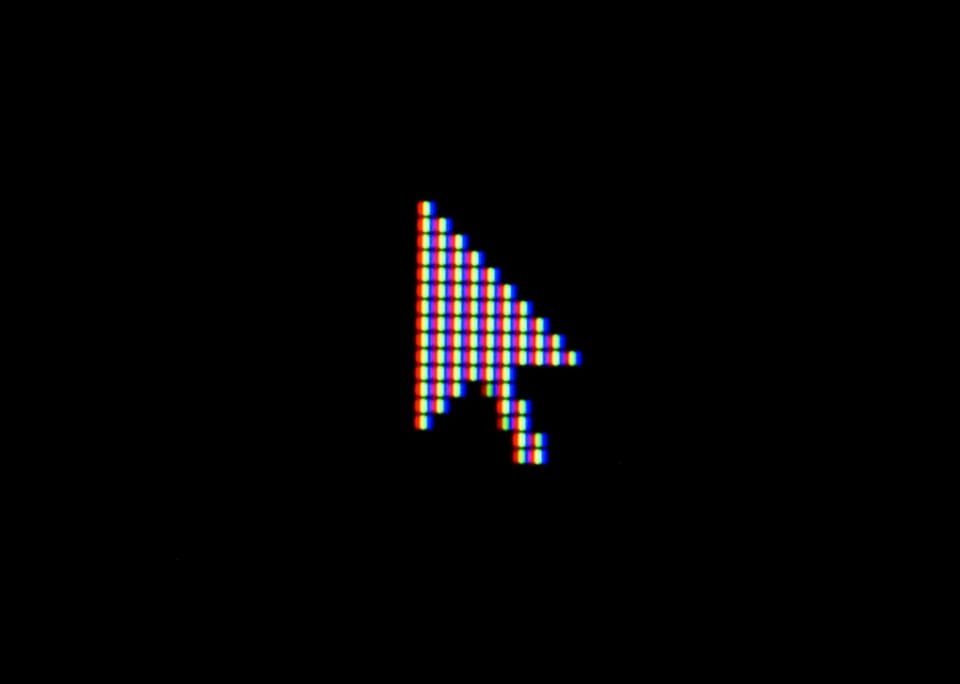

These online trackers, called pixels, are tiny, near-invisible images that are the size of a dot on the display of your device. Even though you can't see them, pixels are packed with tracking code. When you open a webpage that loads a TikTok pixel in the background, the pixel collects information about you, regardless of whether you use the app or have a TikTok account.

As Germain noted, TikTok pixels have been around for years, allowing them to proliferate all over the web. But now under U.S. ownership and with an updated privacy policy as of January, these pixels can collect far more data than before.

Companies like TikTok incentivize website owners to place pixels on their websites under the guise of helping businesses grow, such as providing insights about how their users interact with their content, what they click on, and if it leads to someone making a purchase. In return, TikTok gets to see the online browsing habits of anyone who visits a website containing its tracking pixels, and allows TikTok to track people as they browse the web.

In reality, loading a webpage with a pixel tracker is akin to letting a tech giant watch over your shoulder as you read, scroll, tap, or submit any private or sensitive information to the page.

~this week in security~ is my weekly cybersecurity newsletter supported by readers like you. Please consider signing up for a paying subscription starting at $10/month for exclusive articles, analysis, and more.

As such, there can be unintended consequences of using pixels. Germain found in his tests that several medical, mental health, and other healthcare companies shared information about their website visitors with TikTok, and which pages they viewed, such as fertility tests or looking for a crisis counsellor.

TikTok uses this information to target people more accurately with advertising. But critics say amassing this vast amount of data exposes people to surveillance, or a greater risk of hacks and security lapses, which have happened to ad tech giants in the past.

In fact, it's not just TikTok. Other social media and advertising giants, including Google, Meta (which owns Facebook and Instagram), LinkedIn, X (formerly Twitter), and companies like Mixpanel, rely on pixels to collect people's information as they browse the web, even though they say that website owners are not allowed to collect sensitive data, such as health information.

That said, it still happens and using pixels for data collection across sensitive industries has caught out some big players in the past. Several healthcare, telehealth companies, and health insurance giants have in recent years fallen foul of federal privacy laws by sharing in some cases millions of users' private information with ad giants. In 2024, I exclusively reported for TechCrunch that the website of the U.S. Postal Service was also sharing the private home addresses of logged-in users with Meta, LinkedIn, and Snap. USPS curbed the practice after I alerted the postal service to the security lapse.

There is good news! An ad-blocker is your best defense against invasive online tracking, like website pixels, by preventing the tracking code from loading in your browser to begin with. The good folks at nonprofit news site The Markup in February updated its web privacy inspector tool Blacklight, now allowing anyone to check if a website has a hidden TikTok tracker before visiting.

As Germain's column notes, the solution is ultimately demanding better privacy laws, since this is a problem created and permitted by the ad tech industry. But since hell isn't likely to freeze over any time soon, starving the ad giants of your data is for now one of the better remedies.