I've investigated 'stalkerware' for five years. Here's what I've learned

If there's one thing from my nearly-two decades in journalism I still think about with the everlasting hatred that burns with the heat of a thousand suns, it's "stalkerware."

We've seen countless headline-grabbing phone hacks using powerful government-grade spyware like NSO Group's Pegasus and Intellexa's Predator, which allow police and law enforcement to hack into the most up-to-date iPhones and Androids and snoop on the person's data within.

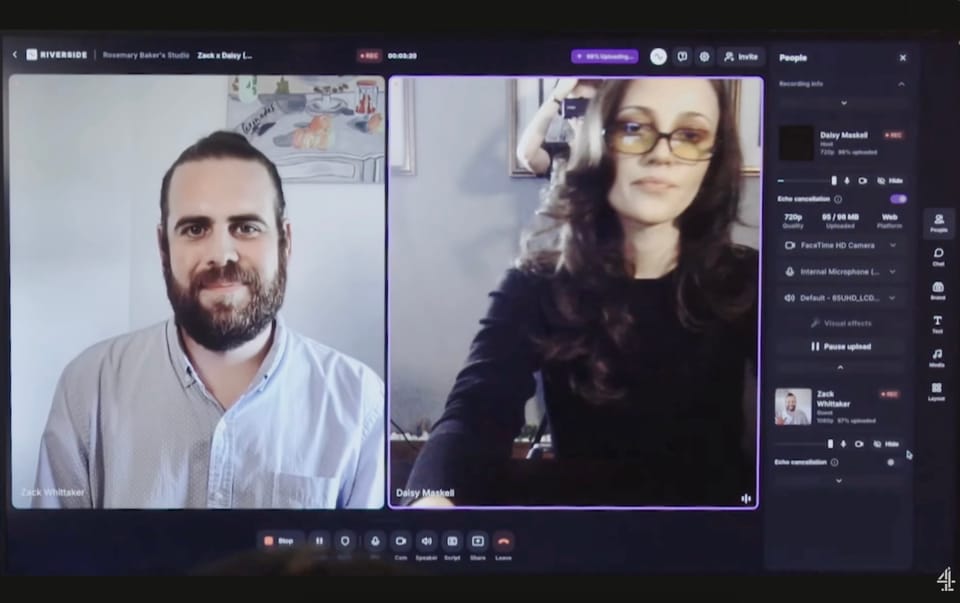

But stalkerware is a far more pervasive and underreported kind of surveillance that exists among civil society today, and it's used widely on people's phones without their consent. So, when a documentary crew from my native U.K. reached out to me earlier this year after reading some of my work investigating this creepy surveillance industry, I jumped at the chance to chat with them.

Stalkerware is a consumer-grade surveillance technology that gives anyone with a credit card the ability to track the phones of people closest to them with the snooping capabilities once reserved for spy agencies. We call it "stalkerware" because it's often used in spousal or family relationships by someone with physical access to a person's Android phone (or their phone's iCloud account). Stalkerware is designed to stay hidden on a person's phone, all the while uploading the victim's photos, messages, passwords, and real-time location data to the stalkerware's servers, and making that data available to the abuser.

As you can imagine, stalkerware is incredibly invasive. It can track what you do, where you go, and who you chat and meet with. Unsurprisingly, using stalkerware against someone without their permission is extremely illegal.

And yet, millions of people around the world use stalkerware every single day to spy on someone else's most private phone data.

I know this because stalkerware has a tendency to have absolutely crap security, and at least 26 operations since 2017 have been hacked, breached, or otherwise exposed the vast amounts of data that they steal from people's phones. I also know this because over the years many of these breached stalkerware datasets have landed on my desk; sometimes by way of an anonymous source dropping a cache of files, and sometimes from a hacktivist who clearly wanted to leave their mark.

I began investigating stalkerware in early 2020 after a security researcher alerted me to a security flaw in a stalkerware operation that was spilling victims' stolen phone data to the public web. As a cybersecurity reporter, I've seen my fair share of alarming cyberattacks and breaches, but seldom had I seen a data leak as sensitive as this one. Seeing the highly personal contents of people's phones just sitting out there on an open web server hit a nerve that would ultimately send me on a multi-year journey to understand how these stalkerware operations worked, how they made money, and to identify the people profiting from them.

At TechCrunch, I have reported on over a dozen stalkerware and other adjacent spyware operations, with the aim of documenting their abuses and exposing the bad actors who run them. I've exposed the real-world identities of shadowy operators through their opsec mistakes; revealed how they use fake U.S. passports to skirt global anti-money laundering rules to make millions of dollars from selling spyware; and — through their own shoddy coding, security lapses, and data breaches — I have documented the global scale of some of these operations and their customers, from serving military personnel to sitting appeals court judges.

~this week in security~ is my weekly cybersecurity newsletter supported by readers like you. Please consider signing-up for a paying subscription starting at $10/month for exclusive articles, analysis, and more.

As such, this work has given me a rare insight into this entire industry, including datasets and financial records from these operations, allowing careful analysis to understand in which regions the most victims are located, where enforcement of the laws are falling short, and to raise broader reader awareness to the issues.

Stalkerware permeates every corner of society and across the world. And, as the documentary makers I chatted with found out and reported in their film, stalkerware is increasingly used in abusive relationships by under-30s to track and monitor their partners. The documentary for the U.K.'s Channel 4, "Controlled: Can I Trust My Partner?" (also on YouTube), deftly explores the ethical, safety, and legal considerations of stalkerware and its many dangers.

I'm thrilled to have participated and to have been featured in the documentary. If you're in the U.K. (or able to be digitally) then check it out; it's worth your time.

The documentary also gave me an opportunity to think back about my investigations and reporting over the past five years about what I've learned. In this article for subscribers, I dive into why stalkerware continues to be a major worldwide threat, how stalkerware operations are able to operate in plain sight, and why countering this kind of surveillance technology is an uphill battle — but why the tide may actually be turning against the stalkerware industry. 👀

Many, many more words for subscribers after the fold… but first:

If you or someone you know needs help, the National Domestic Violence Hotline (1-800-799-7233) provides 24/7 free, confidential support to victims of domestic abuse and violence. If you are in an emergency situation, call 911. The Coalition Against Stalkerware has resources if you think your phone has been compromised by spyware.

If you think your device has stalkerware, I have a how-to guide at TechCrunch that can guide you through what to look for and how to remove it — if it's safe.